What are Bad Chest Genetics?

Bad chest genetics are a measure lifters use to set limits on themselves. The term refers to the idea that someone has limitations that keep them from building a big and strong chest. Most people assume they have lousy chest genetics due to a lack of progress, where, in reality, they haven’t put in the years of hard work and consistency needed.

What Factors Determine Your Chest Genetics?

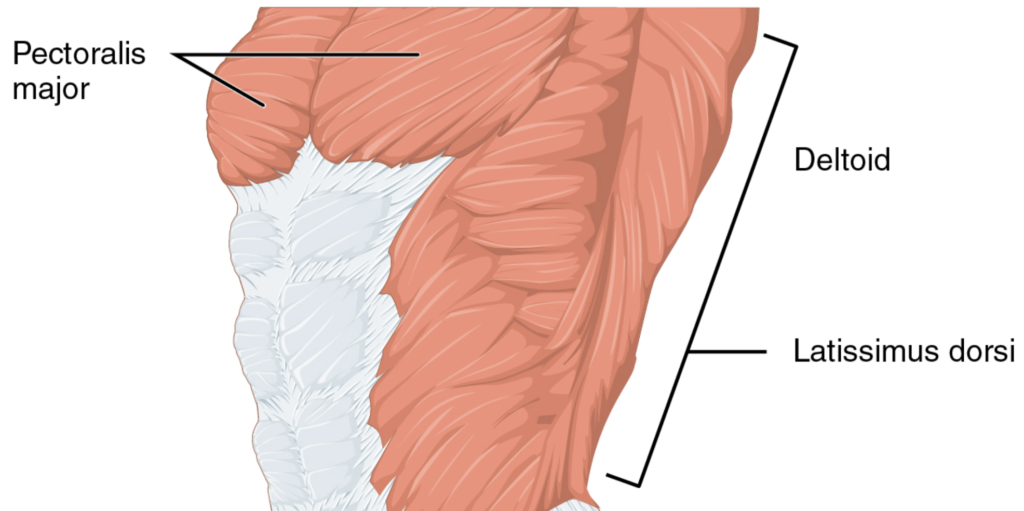

1. Muscle Attachment Points

Skeletal muscle has a (1):

- Origin – the point where the muscle attaches to bone and no movement occurs during contraction, typically closer to the torso

- Insertion – the point where the muscle attaches to a bone and creates a movement when it shortens (contracts)

The sternum is one origin point of the pectoralis major (chest) (2). If someone has longer tendons (strong tissue that connects bone to muscle) where the chest attaches to the sternum, it could create a wider gap between the two pec muscles, making it more difficult to achieve a full inner chest.

2. Muscle Fiber Composition

Muscles consist of slow-twitch (type 1) and fast-twitch (type 2a and 2b) muscle fibers. You can read more about muscle fiber types here. Genetics determine the ratio of slow and fast twitch muscle fibers, with some research suggesting that training may also have an impact (3):

“Current evidence using the most appropriate techniques suggests a clear ability of fibers to shift between hybrid and pure fibers as well as between slow and fast fiber types.”

In other words, doing more explosive training may result in converting slow to fast-twitch fibers, and endurance exercise may have the opposite effect.

The overall ‘makeup’ of your muscles determines:

- Their strengths – for example, a muscle primarily consisting of fast-twitch fibers would have a more significant explosive strength potential

- How they adapt to training – for instance, a muscle consisting of more slow-twitch muscle fibers may adapt positively and grow in response to lower-intensity, higher-rep activities (4)

3. Bone Structure

Your bone structure is the third genetic factor affecting your chest’s appearance. For instance, a wider ribcage provides a greater surface area for the pectoralis major, potentially allowing the muscle group to look more impressive.

In contrast, narrower shoulders and a smaller ribcage with a smaller surface area cannot support as much muscle mass.

Do You Really Have Bad Chest Genetics?

Lifters often cast a critical eye on themselves and rush to conclusions. So, let’s answer some questions to help you determine whether you have bad chest muscle genetics.

1. Do You Train Correctly?

When faced with a lagging muscle group, the most crucial question is, “Am I training that muscle well enough?”

In other words, are you doing enough sets, split between two to four exercises that target the chest from different angles and in different rep ranges? Do you train at a high enough RPE (close to failure), and does the chest feel tired by the end of each set?

Have you seen improvements in your performance in recent months: doing more reps, lifting more weight, or lifting the same amount but with more control and a smoother form?

We highly recommend using the Hevy app to log your workouts and easily see if you’re making progress over time.

2. Are Other Muscles Growing?

Another question is, “Are other muscles getting noticeably bigger and stronger while my chest stagnates?”

This is important to know because you may assume you have bad chest genetics because this is likely the first muscle group you notice when you look in the mirror. “My chest hasn’t grown one bit––it must mean I have bad chest genetics.”

Other muscles, especially those in the back (lats, rhomboids, traps, lower back, glutes, hamstrings, and calves), may also not grow, but you’re less likely to notice.

So, before concluding, take your time to measure whole-body growth through progress photos, circumference measures, and gym performance. That way, you can more confidently tell whether it’s just your chest that’s lagging.

3. Do You Train with Proper Form?

Activating the chest and making it do most of the work can be challenging, especially for less experienced lifters.

Rather than training your chest during the bench press, dip, push-up, fly, and other movements, you may emphasize the shoulders, triceps, and even the serratus anterior.

As a result, your chest may not grow at the desirable rate (or at all), and you may think it’s because of bad genetics. Improving your technique could lead to better chest muscle activation and growth.

Before We Move Forward

The truth is that it’s nearly impossible to tell if you have good or bad chest genetics without spending years of your life training hard and eating for muscle growth. Most people don’t put nearly as much effort as they should before jumping to conclusions.

This way of thinking leads to limiting beliefs like, “Why bother? I have bad chest genetics, and that muscle will never grow.” This mindset leads to less effort and inconsistent training, essentially becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy: you get bad results because you expect to.

How to Get The Most Out of Your Chest Genetics

While it’s impossible to fix bad chest genetics, it’s also counterproductive to conclude you’re not meant to have a barrel chest. So, let’s look at the nine things you can do to improve your odds:

1. Do Enough Sets

There is a tight correlation between the number of sets we do and the growth we can expect. It’s common knowledge that doing more work leads to better results, so long as you can recover well between workouts.

Research also supports the idea, with a recent systematic review that examined six studies concluding (5):

“According to the results of this review, a range of 12-20 weekly sets per muscle group may be an optimum standard recommendation for increasing muscle hypertrophy in young, trained men.”

It’s best to start with fewer sets (around 10-12) per week to see if that’s enough to see growth, especially at the start of a new training program. Why? Two reasons:

First, you may be able to grow well by doing less work so long as other variables (such as effort, progression, and technique––more on those in a moment) are in check. Second, starting with less volume would allow you to increase the number of sets you do should you stop growing later.

For example, if you stop seeing results from 10 weekly sets, you can increase to 12 for a few weeks and see if that’s enough.

2. Do at Least Three Exercises

A minimalistic training approach where you do just a handful of exercises for your entire body can work. But would that be ideal? In most cases, no. There are several reasons why:

First, doing just a handful of exercises for the whole body gets boring after a while. That could affect your motivation, consistency, and the effort you put into workouts.

Second, a single exercise is typically insufficient to effectively target one muscle and cause balanced growth. Even small and seemingly simple muscles like the biceps and calves benefit from exercise variation.

For example, the calves may grow better when you do a seated and a standing calf raise.

The same goes for the chest. You should do a flat bench press to target the lower and middle portions and an incline press or fly to develop your upper chest (6).

Third, doing countless sets of the same exercise (especially a tough one like the bench press) can lead to aches and overuse injuries because you’re placing high amounts of very specific stress on your joints, bones, and connective tissues.

In contrast, by varying the training stress, your joints and connective tissues are loaded in different ways, and the risk of nagging aches decreases.

To grow your chest muscles optimally, I recommend the following as a good starting point:

- A flat bench press (you can supplement it with a push-up variation)

- An incline press with dumbbells or a barbell––whichever feels better

- A fly movement to isolate the pectoral muscles near the end of a chest workout

Related: Killer Chest and Tricep Workout to Obtain Large Sculpted Muscles

3. Train Your Chest Twice Weekly

Training frequency is somewhat controversial, with some people recommending training each muscle group once per week and others, like Dr. Mike Israetel, claiming that two to three sessions per muscle each week are better.

We could argue in favor of both approaches as each has its benefits. For example, some people enjoy the bro split because it allows them to train each muscle group to exhaustion, doing up to 20+ working sets.

That would ensure an adequate stimulus and make trainees feel they’ve done enough productive training to grow.

However, a higher frequency, like the one Dr. Mike recommends, is generally better for a couple of reasons:

First, it allows you to spread out your training volume more evenly. Rather than doing all your weekly sets for a given muscle in one workout, you can split that into two or three smaller, more manageable doses.

That way, you can do all of your training sets for the chest in a more recovered state and lift more weight for more reps.

Second, we know that protein synthesis rates spike within 24 hours of training and mostly return to baseline within 36 hours (7).

In other words, you may do a few chest exercises on Monday and recover fully by Wednesday or Thursday at the latest. However, rather than training the chest again, you wait a few extra days, essentially losing time your muscles could use to grow.

4. Work Hard

There is no way around it:

Building muscle mass results from a large enough training stimulus, which heavily relies on effort. Without effort, all other training variables would matter to a lesser degree.

Training hard enough forces your muscles to adapt by growing and getting stronger so they can handle the same training stress better in the future.

However, to keep forcing your muscles to grow and get stronger, you must continue putting in effort and creating the necessary overload (more on that below).

One way to track effort is to record your rate of perceived exertion (RPE). You can do so for every set through the Hevy app. RPE is a scale that goes from 1 to 10 and allows you to record the difficulty of each set.

Here’s a quick rundown:

- RPE 10 – you couldn’t do more reps

- RPE 9 – you could do one more rep

- RPE 8 – you could do two more reps

- RPE 7 – you could do three more reps

And so on. It’s worth noting that the lower the RPE, the less likely you are to gauge it accurately. In contrast, going for RPE 7-8+ allows for more accurate recordings.

By tracking RPE, you can more accurately gauge the overall difficulty of your training and determine if you have to make changes because you’re not progressing at the desirable rate.

The problem with RPE and effort is that it’s subjective, which means various factors can influence how you feel at a specific moment and how hard you think you’re training.

Unfortunately, there isn’t that much you can do right away to improve your RPE estimates. You need to gain experience, which comes from recording your RPE values often (especially on compound exercises) and being mindful of how you feel at the end of a set.

For example, as you’re about to finish a set you consider an RPE 8, ask yourself, “Did I genuinely push myself close to my limits, and could I only do two more reps before hitting failure?”

One way to make RPE readings more accurate is to use the occasional AMRAP (as many reps as possible) set. With these, the goal is to push yourself to failure (or very close), which helps you better understand what actual failure feels like.

Additionally, RPE provides a value to work with. For example, if you do an AMRAP set of machine chest presses with 225 lbs and get 16 reps, you’d immediately know what an RPE 8 is: 14 reps.

5. Train With Good Form

Chest growth (or the development of any muscle, for that matter) comes from an adequate stimulus that targets and fatigues enough muscle fibers and generates metabolic stress (8). You may do a chest exercise, but that doesn’t necessarily ensure you’ll adequately train the pectoralis major.

For instance, if you’re doing a flat barbell bench press to develop your chest but mostly feel tension in your shoulders and triceps, you’re unlikely to see the growth you expect.

Your chest needs to feel tired and burning up at the end of a set, and this should be the limiting factor causing you to stop a set when you reach a high enough RPE.

If other muscles fatigue first or you run out of breath, you may not get your chest tired enough to spark growth and strength gain.

The solution here is simple but certainly not easy, as it requires a lot of discipline and mindfulness: you must train with proper form, doing your best to train the chest and feel that muscle group work.

You can also slow your tempo, especially on the bench press, and include a slight pause at the bottom. That way, rather than bouncing the barbell off your chest and making it easier, you force the pectoralis major to do more work to complete each rep.

How Pre-Exhaustion May Help

Another way to fatigue your chest, make it the limiting factor and understand what that feels like (especially if other muscles take over during chest exercises) is to try pre-exhaustion.

For example, you can do a set of chest flyes at a high enough RPE to get your pecs somewhat tired and immediately jump into a set of bench presses. That way, your chest will be more tired than your triceps and shoulders, allowing you to train it more effectively.

I recommend this tactic to test things out and see what you should aim for in terms of chest fatigue. Research doesn’t support pre-exhaustion as a viable tactic to support growth, and it can limit the number of reps you do, reducing your overall training volume (9).

Plus, pre-exhaustion is a more advanced tactic, and I recommend having a spotter in case you get too tired and struggle to complete your final rep.

6. Create an Overload

Good chest genetics are a blessing, but they can only get you so far if your training doesn’t increase in difficulty. This relates to the principle of overload, which states that we must do more work over time (extra weight, more reps, or greater time under tension) to keep growing and getting stronger (10).

Simply put, a given chest routine might lead to muscle gain when you first start. However, as you expose your body to that stress level, it adapts.

Given enough time (it’s difficult to say precisely how much), your body adapts fully and no longer has a reason to continue growing and getting stronger.

You want to avoid this because it gets you to a place where you train somewhat hard and are consistent but fail to see improvements. As a result, you stay the same from month to month (or, in some cases, year to year) and exercise for the health benefits, not to build new muscle.

What does that mean in a practical sense? If you’re currently bench pressing 135 lbs for 5 sets of 5 reps, those numbers should ideally increase over time.

Next month, it might be 145 lbs for 5 sets of 5 reps. Then, it could be 145 lbs for 5 sets of 8 reps. Other ways to progress include:

- Doing the same amount of work but in less time

- Training through a longer range of motion

- Lifting the weight with a slower tempo and more control

- Doing the same training while losing body fat

- Lifting the weight more explosively

- Doing more total sets

- Training your chest more often

In other words, you must do more work over time. One good way to ensure that happens is to log your workouts through the Hevy app. That way, you see how much weight you lift and how many reps you do.

A few simple clicks display a graph of your performance over time, allowing you to see if you’re creating an overload to grow.

Plus, if you record your RPE, you can also track how these things evolve in relation to the amount of effort you put into your training.

For instance, if you previously did 135 lbs for 5 sets of 5 reps at an RPE 8 and can now do 145 lbs for the same reps and sets at an RPE 8, you’ve made progress, and your chest has likely grown.

7. Eat Enough

Muscle growth occurs best when you’re in a calorie surplus (eating more calories than you burn) and slowly gaining weight (11).

For instance, if your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) is 3,000 calories, you should eat up to 3,200-3,250 to fuel your body and see a steady increase in body weight.

Unlike fat loss (which many trainees value more despite being easier to achieve), muscle growth occurs incredibly slowly, and it should be your primary focus if your goal is to build an impressive chest in the long run.

A good recommendation is to allow yourself a week of cutting for every four weeks of productive gaining. So, if you spend 16 weeks in a calorie surplus to build muscle, you can enjoy four weeks of dieting to shed excess fat.

As natural pro bodybuilder Alberto Núñez notes:

“For most people, the body fat percentage where they make the most progress in the most predictable way is not necessarily where they want to be. It’s not their favorite look, and most barely get to that productive ‘zone’ and turn back by doing a mini cut.”

Keep the surplus moderate (no more than 250 calories daily) to maintain a healthy body fat percentage. Overshooting your calorie target too much can cause you to gain too much body fat quickly, forcing you to do a fat loss phase (cut) before you can resume gaining (bulking).

Also, aim for at least 0.7-0.8 grams of protein per pound of body weight (approximately 1.6 grams per kilogram) (12).

8. Recover Well Between Workouts

As mentioned above, doing more work is generally better for growth. For instance, if your diet is in order and you feel recovered but your chest doesn’t grow, the simplest thing you can do is increase the number of weekly sets you do.

However, some trainees take things to the extreme, do too much, and struggle to recover from workout to workout.

Chronic under-recovery limits the muscle’s ability to grow and impairs your performance, making it impossible to create the necessary overload.

In addition to limiting your chest training to twice weekly (as suggested earlier), we recommend doing your sessions at least 48 hours apart. For example, if your first chest workout is on Monday, do the second on Wednesday or Thursday.

That way, your chest has enough time to recover, and you can train harder and create an overload.

9. Give it a Few Years

Our final tip for making the most of your genetics and getting the best possible results is to be patient. As cliche as it may sound, Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither is any physique worth admiring.

Even with good genetics, consistency, effort in training, and dedication to the whole process, it takes years to build a physique you can be proud of.

Too many people jump to the conclusion that they have bad chest genetics after just a few weeks or months of training. This isn’t enough time to accurately tell whether you have good, bad, or average chest genetics.

Focus on the journey and don’t obsess over the outcome as much––you will be far happier and less likely to overthink.

Conclusion

Good genetics are a blessing, but far too many people obsess over their theoretical potential instead of putting in the work.

As a lifter or aspiring bodybuilder, your job is to maximize your training and provide the overload your muscles need to grow. Give yourself a few years of solid effort before concluding you have inferior genetics.

Before you go, check out Hevy––a simple app that allows you to log your workouts in detail, track your progress, and see if you’re on the right track.